Bombed – 4 April 1945

Paul Helmut Kindling

Presented 4 January 2020

Topeka Saturday Night Literary Club*

Season 137

For details and Critique see Slide 42ff

Expanded February 2020

1. Bombers

The modern aerial bomb, with its distinctive elongated shape, stabilizing fins, and nose-fitted detonator, is a Bulgarian invention. In the Balkan War of 1912, waged by Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro – the Balkan League – against Turkey. Bulgarian army captain, Simeon Petrov, adapted and enlarged a number of grenades for use from an airplane.1

Seen here is an RAF store of rows of 500 pound bombs.2

A family note: A more primitive device, a tin can filled with explosives dropped out of a biplane injured one of my uncles in 1917 on the Western Front. He had a permanent limp.

When people think of the Allied bombing of Germany during World War II, “Dresden” automatically comes to mind, not Wesel, Nürnberg or Würzburg or the hundreds of other obliterated German towns and cities. While people debate the death toll at Dresden, more recently determined to have been not 100, but likely no more that 25-30 thousand3, attention is diverted from about 40, 000 civilians killed in the bombing of Hamburg, or the 10,000 in Kassel, the fact that 20% of Nordhausen’s civilian population was killed in a mere fifteen minute attack.

How did this come about? The popular idea that the mission of an air force is to be able to fly over the combat fronts and destroy manufacturing, munitions and other manufacturing sites, factories and and thus interrupt the supply chain. This notion, that the aims of the bombing campaign was to limit the “collateral,” that is civilian, damage, is false, promoted for public consumption. As early as 1941, Charles Portal, commander-in-chief of the UK’s Bomber Command, wrote: “We have caused death and injury to 93,000 civilians. The result was achieved with a fraction of the bomb-load we hope to employ in 1943.”4

By early 1942, there were open suggestions that bombing be directed against German working-class houses, leaving factories and military objectives alone.

This policy was implemented in full in 1942 when, upon his taking over the entire U.K. Bomber Command, Arthur Harris issued the following directive:

“It has been decided that the primary objective of your operations should now be focused on the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular, of industrial workers.” Harris prepared a list of 60 German cities he intended to destroy first: “The aim is the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers and the disruption of civilised community life through-out Germany. It should be emphasised that the destruction of houses, public utilities, transport and lives; the creation of a refugee problem on an unprecedented scale; and the breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts by fear of extended and intensified bombing are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy, they are not by-products of attempts to hit factories.”4

American commanders rejected the idea of city bombing and were skeptical of the claim that such attacks would diminish the German war effort or create a widespread crisis. Portal tried to persuade Ira C. Eaker, Commanding General of the US Eighth Air Force, in February 1943 that round-the-clock attacks on cities would be strategically valuable—“heavy blows delivered on German cities have far greater effect than they did”—but Eaker would not be drawn in.

The different strategic conceptions reflected two different military cultures. American strategic practice was much closer to the German model than it was to the British. At a meeting called in the Air Ministry in March 1943 by Sydney Bufton, then director of bomber operations, the American representative asked for an explanation: “Was it to kill Germans; to cause them to expend man hours; or was it to do specific damage to some certain installation?” It was to neutralize German man-hours.

Although it was initially agreed that the U.S.A.A.F. would carry out daytime raids on military and industrial targets, and the RAF would conduct the nighttime ‘area’ bombing of civilian population centers, nonetheless, the USA joined the British and Canadians to bomb Hamburg in “Operation Gomorrah” and in several later civilian bombings.

2. Bombed

To escape air raids in Berlin, my mother, the two sisters and I spent 1941 winter months in Friedrichshafen at my aunt’s house. You could see Switzerland from there. My father would visit when he could. I went to a catholic school where I did not fit in. The nuns were liberal in the use of the switch: blisters on fingers.

From May to September 1942 my Berlin school class was part of Kinderlandverschickung, a program to ship children away from high air-raid risk cities. By boat we traveled from Berlin to the Baltic Sea resort town Ahlbeck.

Yes, by boat. There are more bridges over waterways in Berlin than in Venice. Well, we swam in the Ostsee, had school and regular class, but I was 11 and severely homesick.

Annegret, my 2 years older sister was sent with her class – no Co-Ed education – to a neighboring village, Bansin. I saw her once briefly that summer. My father visited me in September and informed me I now also had a brother.

The following summer, 1943, I spent on a distant relative’s small farm in a small village in Schlesien. Train to Breslau for overnight at other distant relatives, train to Liegnitz, Striegau, then by horse & oxen drawn wagon to Pläswitz (N51.04 E16.51) now in Poland. My maternal grandfather came from that area. Cousins from Kiel were also there.

Working the fields, learning about farm life was a new experience for this city boy. Now, more removed from the big city, I new even less of what was going on in the world or in the war.

Travelling in September 1943, stopping overnight at other, more distant relatives, I rejoined my mother, sisters Annegret, Marli, Uschi and brother Jochen in Nordhausen, my father’s hometown, to where he had relocated them from Berlin earlier that summer.

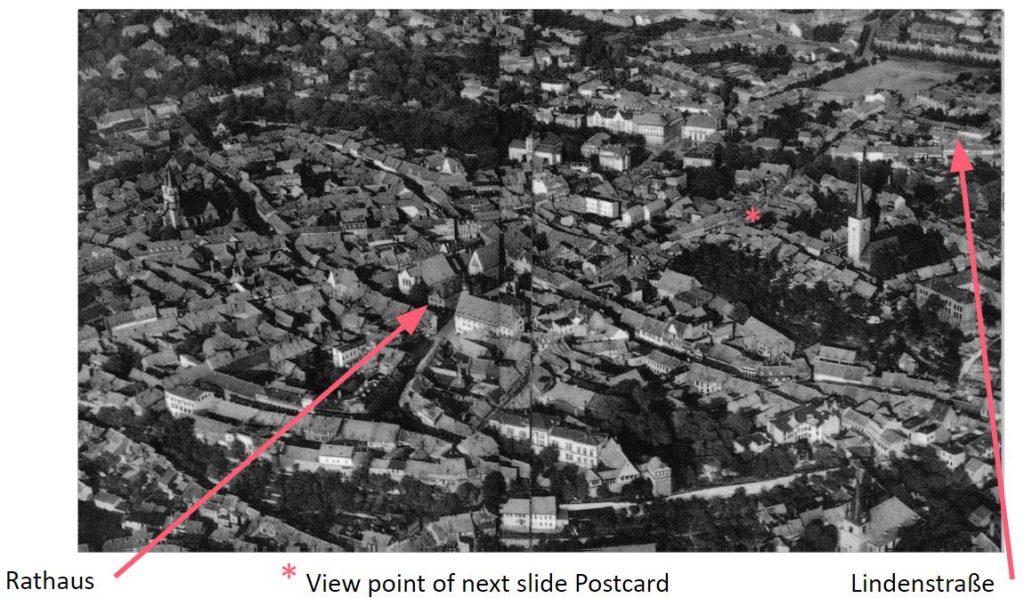

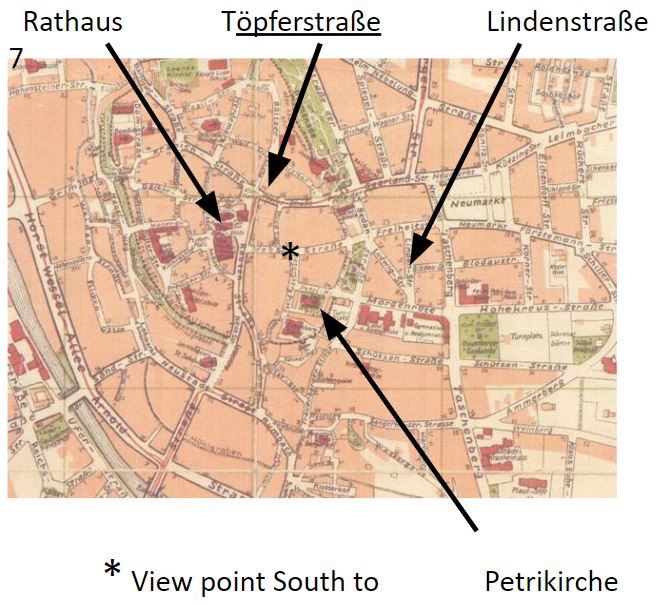

At the Southern reaches and mid area of the Harz Mountains, a geologically old ridge (Brocken 3744 ft) in central Germany, Nordhausen is an important crossroads, terminal of the narrow gauge rail road, with lumber industry, bordering fertile farm lands to the South: Goldene Aue.

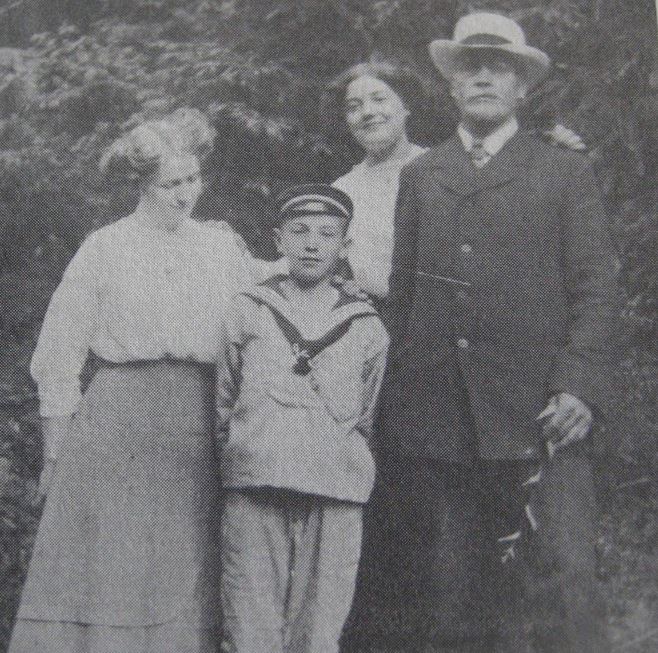

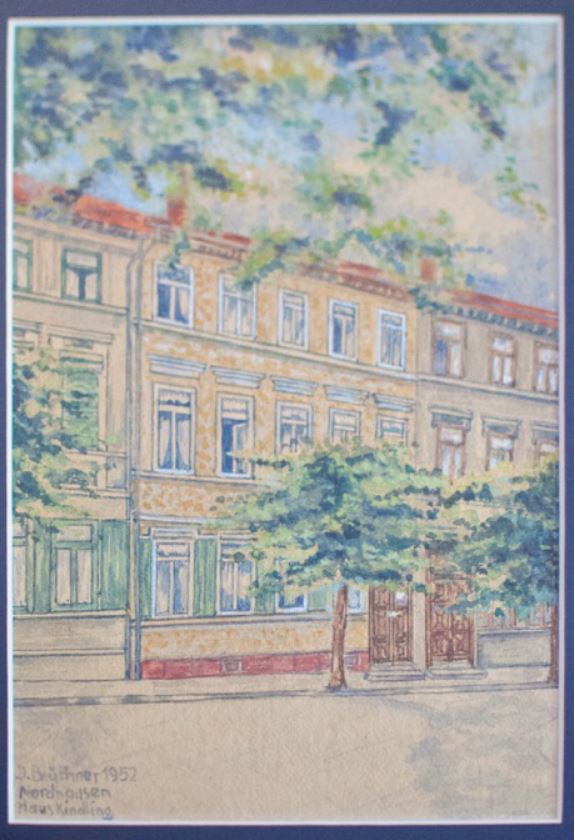

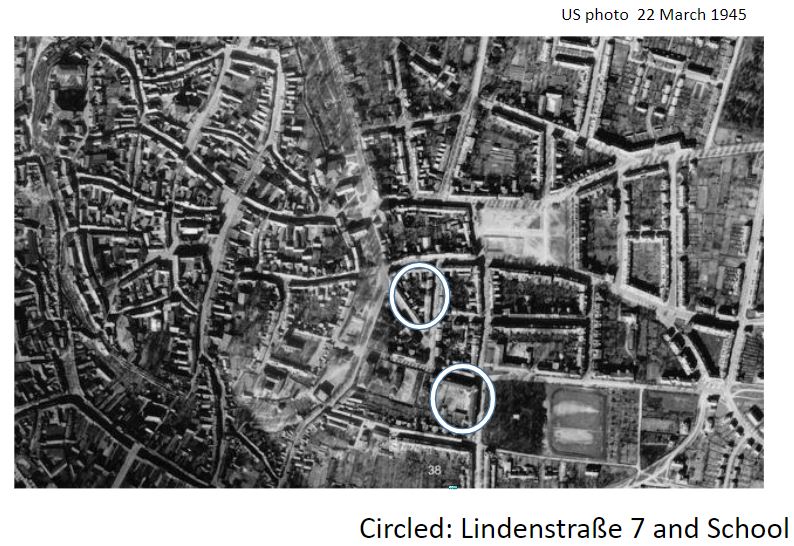

Our grandfather – here with our father, about 11, and his sisters – was manager, buyer for a tool handle factory. The family house (N51.50 E10.80) was close to the center of town. In the archives I found that he is listed as the owner beginning in the late 1890s.

Haus Kindling

Lindenstraße 7

Nordhausen am Harz

Owned by Kindling Family since 1890s as it existed before its destruction.

Painted in 1952 by long time family friend:

Dorothea Bluethner

Life was quiet in this 1000 year old city of about 40,000, away from the frequent night time visits to the air raid shelters in the cellars of the apartment building in Berlin. School was just up the street.

As a stranger in class,

a skinny short kid, not speaking the local dialect, I was bullied and often beaten up.

Yes, we did have to participate in the “Hitler Youth” activities, but for me this was at a riding stable, learning, riding and taking care of the horses.

The previous summers I did not have access to a radio and did not know what was happening in the war. I had missed news about Hamburg’s destruction. We had lived in Hamburg from 1935 to 1937.

Here in Nordhausen I could follow the news and go to movies.

We rode the narrow gauge railroad into the Harz mountains, and in the winter did some skiing. I attended many symphony concerts.

My father would be there now and then. We went hiking as he had done in his youth, sometime pick up a bag of cherries and have a pit spitting contest.

My classmate next door and I rode our bikes in the surrounding countryside. Once, on our way back from a more northwesterly excursion, we rode along a large fenced-in area. We knew it was some sort of a camp. Only later did I learn it was “Mittelbau Dora” concentration camp, near the Kohnstein mountain, where, in tunnels, under horrible conditions, inmates were forced to assemble A4 and other rockets.

I do not recall many air-raid drills or alarms. However, I now read there were many because the city was on the route bombers took towards Berlin and the Mid-German industrial areas. I do remember on a 1944 Sunday walk in the nearby country seeing a huge, precisely lined up, formation of silvery planes, droning high overhead on a Northeast course.

We felt generally safe, thinking this old city could not be a target. I remember listening to the radio, following the progress of the Allied forces from the West and across the Rhein. We knew the war would not last much longer.

In early March 1945 I was ordered by the Hitler Youth group to attend a leadership course for a week in the town of Ruhla, Thüringen, 100 km or so Southwest (N50.89 E10.37). I did not want to go, but my mother insisted, because to refuse would get the family into very serious trouble. So I went. Once there two days, however, as the US forces were approaching, the school was terminated and we were told to leave.

I walked, jumped on freight trains, and hitchhiked to get back home.

Easter was April 1, vacation had started. On Tuesday, the 3rd of April, my neighbor and I went to a movie in the Western part of town. Soon – we had watched only the lead-in strip – the air-raid alarm sounded and we were running home, up the well worn steps to the center of town, through the narrow streets along the old houses.

It was in the narrow, curvy Töpferstraße where we encountered the tracer rounds exiting the front of the low flying planes, bullets pockmarking the walls of the shops and houses.

We dashed into the nearest building, a butcher shop. When it was quiet, we could get home. There had been little damage.

We did not know this then, but damage was severe Southeast of us.

247 Lancaster bombers and 6 Mosquitos of the British 1st and 8th Bomber Group had dropped 1,700 tons in 20 minutes.

The Boelcke Kasernen, barracks were hit.

Bomber Command Diaries “… to attack what were believed to be military barracks near Nordhausen. Unfortunately, the barracks housed a large number of (sick or too weak to work) concentration camp prisoners and forced workers… The bombing was accurate and many people in the camp were killed; the exact number is not known.”5

It was about 400, the next day 600 more.

In the morning, Wednesday April 4th, shortly after 9, alarms sounded again.

All to the cellar.

Sitting under its curved ceiling, cramped in the small space between the lattice slatted storage places (one for each apartment), we were twelve:

Two ladies from the ground floor apartment, my father’s 80 year old uncle Otto and wife Gertrud from the third floor, his two sisters, Grete and Annie, my older, Annegret, and two younger sisters, Marie-Luise and Ursula, my mother and younger brother Jochen, now 2 and a half, and myself, we all from the second floor and the “Hinterhaus.” I was the last one down and faced the stairs.

Bombs were screeching and when exploding nearby felt like earthquakes. After some more of that, the cellar door flew open. Then, an explosion pushed it inward through its frame, bricks, dust and debris tumbling down the stairs towards us.

We were quiet and no one moved, my mother holding the two youngest.

The two ladies from the lower apartment kept praying at full volume, as if to drown out the noise of the screeching, exploding bombs.

After a long 20 minutes it was over.

Except for more debris drifting down, windows blown out, and holes in walls here and there, the house remained standing.

There had been direct hits on houses nearby, up and down the street.

Across the street, I saw death for the first time.

In the span of those twenty minutes another 1200 tons of bombs and incendiary devices had been dropped by 252 Lancasters and Mosquitos.

Fires were not far and it was immediately clear we would have to get out.

No, we did not have bags packed. My mother sent me upstairs to quickly pack a few things, but what I packed made no sense, and we soon lost the bag anyway. We headed East. I believe my parents had previously decided the direction. My aunts went North. It would be some years before we would see them again.

About a block away we met a woman I would never forget. She was scurrying along as were we. Small, dressed in very loose fitting striped clothing, skin and bones, she could not have weighed more than 80 pounds. As I later concluded she had been an inmate from the Boelcke Kaserne.

Her image, a message in a way, has been with me these 75 years, never far away.

Getting out of town was not so easy. My brother was in a baby buggy – some of the time. There were bomb craters in our path – my sister remembers – mud form previous rains, and It took a long time to reach the already overcrowded village of Leimbach. (N51.50 E10.86)

The city had emptied and in the afternoon, evening and night most of it was consumed by an inferno, the timbered wood buildings readily going up in flames.

About 8800 died in those two days, among them some 1200 in the Boelcke Kasernen. Three out of four dwelling places were destroyed.

Four days later my sister and I went back.

Only still hot rubble remained of the houses on Lindenstraße and Blödaustraße.

Part of a wall of our house remained standing and the curved, vaulted ceiling had held.

I climbed down into the cellar: ashes.

As we were leaving we heard, then saw more airplanes overhead, bombs dropping, screeching, then exploding a block or two away, kicking up debris, floating in our direction.

Was there anything to hit but rubble?

3. After

Six days later the Americans came. They discovered the horrendous conditions in the Boelke Kasernen and in the concentration camp Mittelbau Dora, Northwest of the city. The dead were buried in mass graves. Typhus soon came and very slowly people returned. We did not.

My father had found us in Leimbach, taken us Northeast and left us in a small town, Nienburg/Saale. (N51.86 E11.77).

We knew no one there.

Some 70 days later, near the end of June, he came for us so we ultimately reached Kiel and family.

In Kiel large sections had also been destroyed. The ship yards had been targets and at the 24 August 1944 raid, worst of the 633 air raids the city experienced, some 1300 bombs and 100,00 incendiary devices fell.

For a short while we stayed with my aunt all in a two bedroom apartment and then found rooms in the cellar of the in-the-country house of a family friend where we lived until we could emigrate to America in 1950.

On 2 July 1945 Nordhausen became part of the Soviet Zone. The iron curtain had fallen.

Soon the teaching was that it had been the Americans who had done the bombing, killing all the people, destroying the old city. History was rewritten to suit the new regime. – Does it not seem history is always being re-written?

This is how it was in the entire Soviet Zone and the later DDR. After living under the Nazi dictatorship, in these Eastern provinces one destructive 13 year dictatorship was replaced by another, perhaps only less destructive in the physical sense, but destructive of freedom and progress.

And this authoritarian regime lasted 45 years!

Now the city is rebuilt, there is more industry, a technical university. It has become the major commercial and transportation hub for the Southern Harz region.

Now the Straßenbahn tracks connect to the Harzquerbahn, the narrow gauge – 100cm – railroad across the Harz mountains. Some of the street cars have both electric and Diesel motors and travel on both systems, a first in the world.

This type of combination is now known as the: “Nordhäuser Modell.”

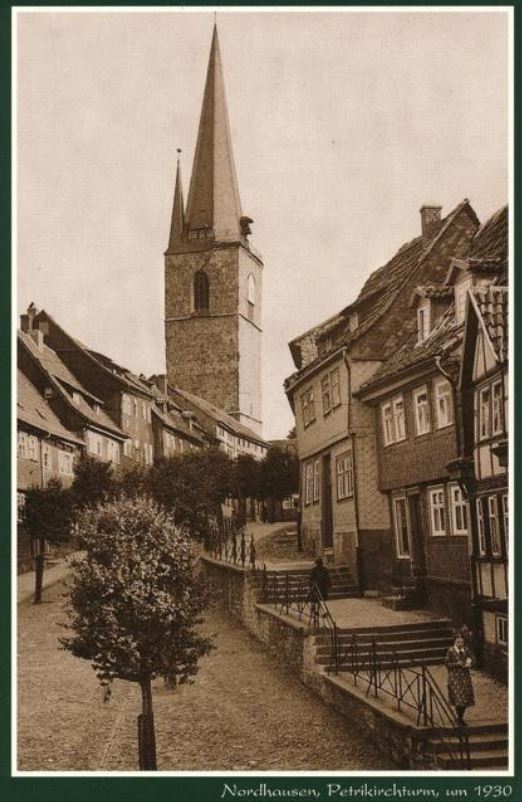

The Petrikirche had been destroyed, but as the walls of the tower remained, the steeple could be rebuilt, seen here between two of the many new, more attractive, more modern apartment houses.

Still made is the traditional, double distilled Nordhäuser Dopplekorn.

There is a Weihnachtsmarkt, and now Nordhausen is like any other city in Germany, people live and work, travel, make art, music and live lives as we do.

However, now, even 30 years after reunification, there remains significant resentment of “Westees.”

10 December 2019

When one googles Nordhausen now, the majority of the first 10 pages are about Mittelbau Dora, the concentration camp, the slave labor, the atrocities, the Boelcke Kasernen.

And the part Nordhausen had in the vast network of the holocaust, is what 1945 Nordhausen remains about, not so much its destruction and the inferno.

Reminders came often – in the form of unexploded bombs found buried under rubble or at the time of new construction. As recently as November 2019 about 15,000 people were evacuated from the city center so one could be safely defused.6. Some of the narrow old streets were widened – the old Kornmarkt is now a roundabout – new buildings were built and older ones reconstructed where possible.

And now there are ever fewer who remember the bombing. The bombing is but a part of the city’s long story and in seven years the arc of its history will pass the 1100 year mark.

In a lower area in the West, near the river, some streets had been spared in the inferno. Here one can get a feel of the city as it had been before.

I began by touching on the moral issues of bombing civilians during war.7 Recently a friend said that he considered the bombing campaigns waged by America and Britain during the war to have been war crimes. That word does not make sense. War is the crime.

After I spent a few days in Nordhausen in early December 2019, read in the archives8 and in a real bookstore9, walked the cobblestone streets, rode the streetcar lines end to end, attended a concert, talked to many people, all strangers, the city and its history came into a different sort of focus for me.

A migrant when I came in 1943, I left Nordhausen a migrant after the bombing in 1945, not to return. For me, then the 14 year old, having just seen death across the street, leaving the destroyed city meant we had escaped, we had survived. My roots are not in this city and I do not speak the dialect, yet over these 75 years since then, the fact and circumstances of that survival, in that city, on that April day in 1945, has continued to grow in significance, has informed my outlook, my Weltanschauung, has immeasurably enhanced my appreciation of my family and of my sibs who share that survival, and has lead to a greater love of this amazing, wonderful existence we call life.

Sources, additional reading:

1. Overy, Richard. The Bombers and the Bombed. Prologue.

2. Overy, Richard. The Bombers and the Bombed. Pg 194

3. Taylor, Frederick. Dresden, Tuesday, February 13, 1945

4. Overy, Richard. The Bombers and the Bombed. Pg 92

5. Martin Middlebrook und Chris Everitt: The Bomber Command War Diaries. Midland. 2011. S. 691/692

7. There is now a very large literature on these issues. See, e.g.,

Anthony Grayling, Among the Dead Cities: Was the Allied Bombing of Civilians in World War II a Necessity or a Crime? (London: Bloomsbury, 2005);

Jörg Friedrich, Der Brand: Deutschland im Bombenkrieg, 1940–1945 (Munich: Propyläen Verlag, 2002);

Nicholson Baker, Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II and the End of Civilization (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008);

Stephen A. Garrett, Ethics and Airpower in World War II: The British Bombing of German Cities (New York: St. Martin’s, 1993);

Beau Grosscup, Strategic Terror: The Politics and Ethics of Aerial Bombardment (London: Zed Books, 2006); Igor Primoratz, ed.,

Terror from the Sky: The Bombing of German Cities in World War II (Oxford: Berghahn, 2010).

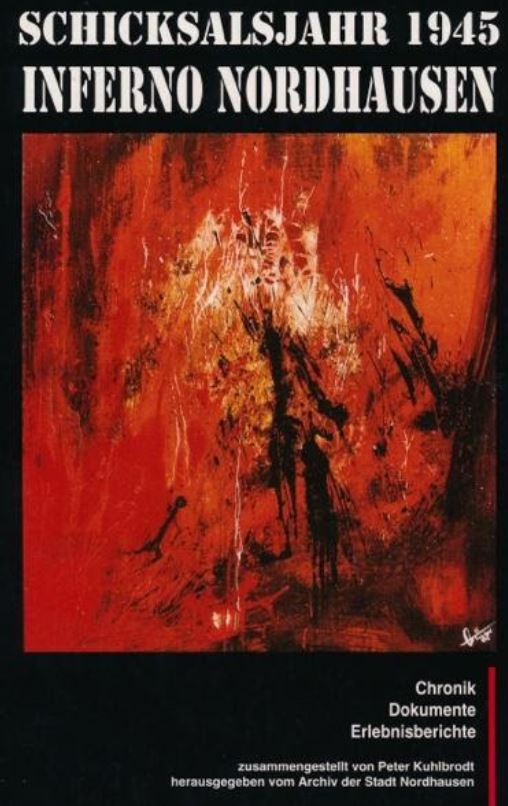

8. Kuhlbrodt, Peter: Inferno Nordhausen. Schicksalsjahr 1945 (Heimatgeschichtliche Forschungen des Stadtarchivs Nordhausen, Harz. Band 6). Archiv der Stadt Nordhausen, Nordhausen 1995, ISBN 3-929767-09-0

9. https://rosebuch.buchhandlung.de

Some slides were copied from:

Nordhausen, Luftbild-Atlas, 1935-1945

ISBN 978-3-95966-283-3

Verlag Rockstuhl, D-99947 Bad Langensalza,

Some slides were copied from Wikepedia pages or Google Earth.

Other photos are from my personal collection.

I appreciate the assistance of Dr. Wolfram Theilemann in the Stadtarchiv.

Herr Dietrich Rose extensively searched and obtained reference material.

*Founded in Topeka, Kansas in 1883, in the post-Civil War era of articulate literacy and enthusiasm about the democratic process, The Saturday Night Literary Club kept some of its customs reflecting that era: a member is identified with a State and addresses the Chair as in a legislative assembly.

Motto: “Don’t Take Yourself So Damn Seriously.”

Introductions and critiques are given by other members of the club and a general discussion follows each presentation.

Essays are collected at the Kansas Historical Society. The collection also includes documents pertaining to the opening of membership to women in 2011, end of year program announcements, and a New Member handout:

“The Saturday Night Literary Club–A History, 1883-2010.”

Call Number: Manuscripts Collection 819 Unit ID: 45688

See also:NY Times: https://www.nytimes.com/1988/03/18/us/topeka-journal-a-club-where-egos-are-kept-small.html

First slide at time of presentation:

Madam President, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Club.

Recounting personal experience in an essay here has generally not been on the preferred list of topics, unless this also leads to a more substantive understanding of a particular subject matter.

I do not think this essay does that, in contrast to one by my former neighbor, long time member of this club, Jean Reeves, reporting on his service as commander of a prisoner of war camp in Germany after World War II, and recounting his experiences with his Russian counterpart, when he discussed – with foresight -implications for future American – Russian interactions. That essay resides with all others from this club in the Archives of the Kansas Historical Society. They are begging to assume digital format.

*End of Essay

Introduction of Essayist and Critique of “Bombed” by the Member from Germany, 04 Jan 2020

by Ted Daughety, the Member from South Carolina

Madam President, Mr. Essayist, Officers and Members of the Club:

I was invited to apply for membership in this club by the recently deceased Member from Virginia, Ralph Skoog. Once I had become a member, he advised me always to choose a topic for an essay different from my professional expertise, in order to learn from the exercise. He advised that I choose an introducer who knows me the best, and a critic who knows the topic the best.

Until I arrived to see his daughters here, I thought I might be a reasonable choice to introduce Paul Helmut Kindling, the Member from Germany. I worked elbow to elbow with him for several years in the Stormont-Vail ICU. I was there when he pushed for membership in the Club for women, well ahead of interest in such by the President and Parliamentarian of the Club at the time. I have had lunch with him most Saturdays in the decades since. I have chosen not to review his education between the events of tonight’s memoir and his arrival in Topeka as a well-trained surgeon, as they have been listed in introductions of his previous essays.

I most certainly am not one who knows this topic well, while one can find no more authority than that of the primary source of the events from which we heard tonight. I wish that the recently deceased Member from Alabama could be here to critique the essay from his perspective of having been a US Air Corps bomber navigator, with many missions over Germany. I can only claim to have given the essayist a copy of The Bombers and the Bombed when it was first published, which may have contributed to his choice.

There is no criticism for the clear recording of an experience of such significance as was depicted in the memoir we heard tonight. I would not presume to try. What I would like to do is to place the events in a context drawn from some books that I have read recently, which might prove of interest.

R.J. Rummel, author of Death by Government coined the term democide, defined as “the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command.” That is what we are discussing tonight, the intentional killing of unarmed civilians by governments.

Rummel estimates that in the 20th century, 262 million people died by democide, as a result of Lenin’s and Stalin’s purges, Stalin’s and Mao’s famines, population bombing from Guernica to London to Dresden, Nazi and Pol Pot holocausts, genocide in Ruanda, and many others, or 6 times as many as died as soldiers in every war. Rummel tested the correlation of the number dead with types of government, and historical setting of the events. “Case studies and quantitative analysis show that ethnic, racial, and religious diversity, economic development, levels of education, and cultural differences do not account for this killing. Rather, democide is best explained by the degree to which a regime is empowered along a democratic to totalitarian dimension and secondarily the extent to which it is characteristically involved in war or rebellion.”

The essayist attributed to Air Chief Marshals Sir Charles Portal and Sir Arthur Harris, the latter known by the press as Bomber Harris, within the RAF as Butcher Harris, the decisions to begin murdering civilians to attack popular support for the war effort. He rightly noted that it took longer for the US Air Corps to target civilians, possibly taking longer American experience with loss of sons and daughters, longer consideration of truly existential threat. It also took the emotional distance of bombing to accept murdering civilians. Nonetheless, those decisions contributed to the deaths of 353,000 German [Overy 307] and 53,600 French civilians [Overy, p400] by Allied bombers, over 100,000 by American bombers.

Matthew Carr has suggested that the American pattern of murdering civilians to destroy the morale of an adversary began by the winter of 1864, when Gen. William T. Sherman shifted from protecting civilian lives and property in war zones to destroying everything in his path, including Meridian, MS, Atlanta and Savannah, GA and Columbia, South Carolina. He provides examples of that scorched earth destruction of civilians’ property and lives in American campaigns in the American Indian wars, Phillipines, Korea, VietNam, and of course, as described by the essayist, in World War II, particularly in Germany and Japan.

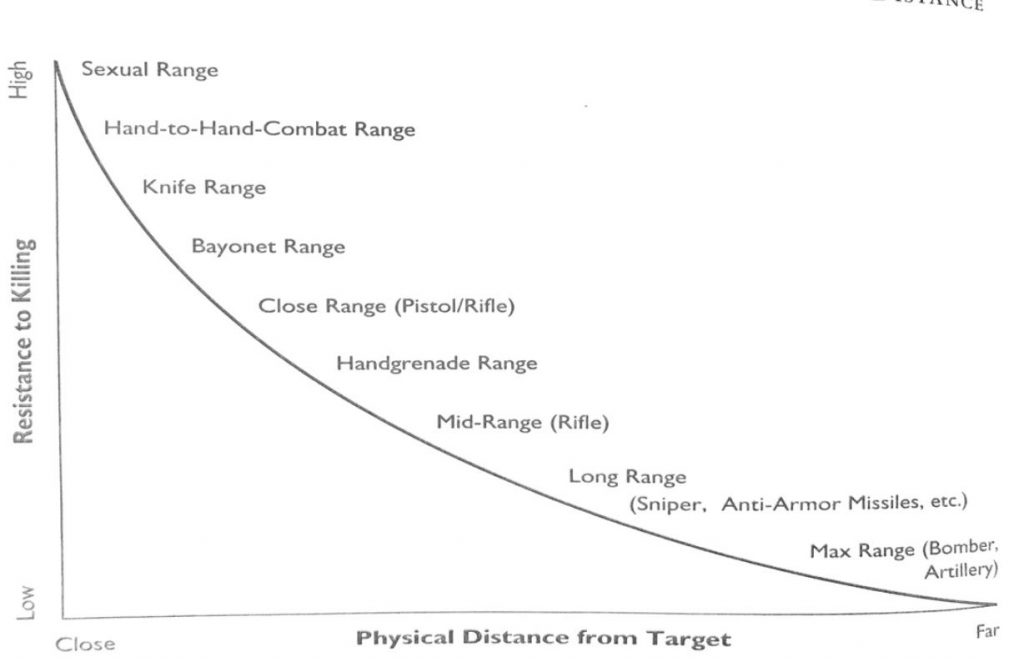

But what have we learned from intentionally targeting civilians with bombing? It is not clear to me that there is a recognition that democide is against the Geneva conventions, that democide boosts adversary morale, or even that killing by bombing has the same impact on an individual as the killing pictured by Chief Eddie Gallagher, or by the strangulation and dismemberment as of Jamal Khashoggi. Lt. Col. Grossman deals at length with the variation of the psychological response to killing with distance from the victim. [See his graph of difficulty training military to kill by various methods, p. 98].

Daniel Ellsberg contends that the Doomsday War Plan that he and the other RAND consultants created for the US Air Force, remembered as the Mutual Assured Destruction of the Cold War with the USSR, remains in place, and with more hair triggers than is popularly recognized. Our current President is overtly preparing for war in space in his inauguration of the US Space Force. Our history, our preparations, and Ender’s Game would suggest that we all are at significant risk unless we learn from the experience of the Member from Germany.

Bibliography

Overy, Richard. The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied air war over Europe, 1940-1945.

Viking Penguin, New York, NY, 2013.

Carr, Matthew. Sherman’s Ghost: soldiers, civilians, and the American way of war.

The New Press, New York, NY, 2015.

Grossman, Dave. On Killing: the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society.

Back Bay Books, Little, Brown & Company, New York, NY, revised edition 2009.

Ellsberg, Daniel. The Doomsday Machine: confessions of a nuclear war planner.

Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.Card, OS. Ender’s Game. Tom Doherty Associates. New York, NY, 1977.